Volume 87, Number 4, October 2006

Volume

87, Number 4, October 2006

Cover

Photo: Herbivory on the species-rich tropical genus Inga is largely restricted to young leaves. On Barro Colorado Island, Panama (BCI), with 11 common species of Inga, many caterpillar species attack only 1–4 species of this genus. A single species of gelechiid caterpillar fed on 10 species of Inga. Observations of this caterpillar’s feeding patterns showed that the availability of young leaves, competition from other herbivores, and to some extent parasitism rates determined preferences among the various species of Inga. Ants visit the leaves during the day to feed on the extrafloral nectaries of Inga leaves, but evidently do not deter use of the leaves by caterpillars. The authors found no correlation between the abundance of the gelechiid and the numbers of aggressive ants on the leaves. It appears that leaf rolling (not illustrated here) discourages parasitism and interference by ants to some degree. This photograph was taken in connection with the article, “Food quality, competition, and parasitism influence feeding preference in a neotropical lepidopteran” by Thomas A Kursar, Brett T. Wolfe, Mary Jane Epps, and Phyllis D. Coley, tentatively scheduled to appear in Ecology 87(12), December 2006.

Cover

Photo: Herbivory on the species-rich tropical genus Inga is largely restricted to young leaves. On Barro Colorado Island, Panama (BCI), with 11 common species of Inga, many caterpillar species attack only 1–4 species of this genus. A single species of gelechiid caterpillar fed on 10 species of Inga. Observations of this caterpillar’s feeding patterns showed that the availability of young leaves, competition from other herbivores, and to some extent parasitism rates determined preferences among the various species of Inga. Ants visit the leaves during the day to feed on the extrafloral nectaries of Inga leaves, but evidently do not deter use of the leaves by caterpillars. The authors found no correlation between the abundance of the gelechiid and the numbers of aggressive ants on the leaves. It appears that leaf rolling (not illustrated here) discourages parasitism and interference by ants to some degree. This photograph was taken in connection with the article, “Food quality, competition, and parasitism influence feeding preference in a neotropical lepidopteran” by Thomas A Kursar, Brett T. Wolfe, Mary Jane Epps, and Phyllis D. Coley, tentatively scheduled to appear in Ecology 87(12), December 2006.

Visit the Photo Gallery for more photographs submitted by our scientific journal authors.

Table of Contents

(click on a title to view that section)

Governing

Board

ANNOUNCEMENTS

Society Notices

Call for Nominations: ESA Awards

Student Awards for Excellence in Ecology

2006 Student Award Judges

NSF Student Travel Awards

Resolution of Respect: Syunro Utida

SOCIETY ACTIONS

ESA Awards for 2006

Murray F. Buell Award

E. Lucy Braun Award

Robert H. MacArthur Award

William S. Cooper Award

George Mercer Award

Eugene P. Odum Award

Sustainability Science Award

Corporate Award

Honorary Member Award

Distinguished Service Citation

Eminent Ecologist Award

Minutes of the 8–9 May Governing Board Meeting

ANNUAL REPORTS

Reports of the Executive Director and Staff

Executive Director

Finances/ Membership/ Administration

Annual Meeting

Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment

Development Office

Public Affairs Office

Science Programs Office

Education and Diversity Initiative Activities Office

Publications Office

Reports of Officers

Vice President for Education and Human Resources

Reports of Standing Committees

Awards Committee

Board of Professional Certification

Meetings Committee

Professional Ethics and Appeals Committee

Publications Committee

Shreve/Whittaker Awards Committee

Reports of Sections

Applied Ecology Section

Aquatic Ecology Section

Asian Ecology Section

Biogeosciences Section

Education Section

Long Term Studies Section

Paleoecology Section

Physiological Ecology Section

Plant Populations Ecology Section

Rangeland Ecology Section

Soil Ecology Section

Statistical Ecology Section

Student Section

Traditional Ecological Knowledge Section

Theoretical Ecology Section

Urban Ecosystem Ecology Section

Reports of Chapters

Canada Chapter

Mexico Chapter

Mid−Atlantic Chapter

Rocky Mountain Chapter

Southeastern Chapter

PHOTO GALLERY -- Images from articles in our scientific journals

Feeding Preferences in a Neotropical Lepidopteran. T. A. Kursar, B. T. Wolfe, M. J. Epps, and P. D. Coley

Assessing Tiger Population Dynamics. Ullas Karanth, James D. Nichols, N. Samba Kumar, and James E. Hines

CONTRIBUTIONS

Commentary

Some Reflections on ESA: Then and Now. G. E. Likens

A Response to the ESA Position Paper on Biological Invasions. B. P. Caton

A Reply to B. P. Caton’s Response. D. M. Lodge, D. A. Andow, P. D. Boersma, and R. V. Pouyat

Adding Ecological Considerations to “Environmental” Accounting. D. A. Bainbridge

A History of the Ecological Sciences, Part 22. Early European Naturalists in Eastern North America. F. N. Egerton

Rachel Carson and Mid-Twentieth Century Ecology. W. Dritschilo

DEPARTMENTS

Public Affairs Perspective

Congressional Staff Get Their Feet Muddy with Wetlands Scientists

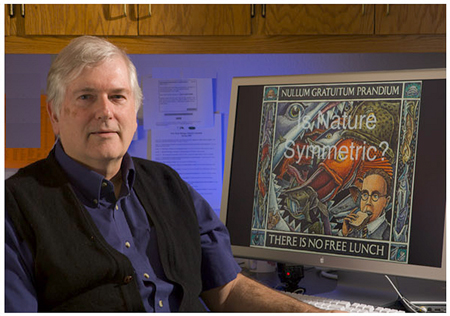

Best MAMAs (Maxims, Analogies, Metaphors, ...) Contest, and Contest Outcomes

REPORTS OF SYMPOSIA AT THE ESA ANNUAL MEETING

Ecological Effects of Gulf Coast Hurricanes. C. Jackson

What is an Icon? A. M. Ellison

Urban Fodd Webs: Predators, Prey, and the People Who Feed Them. P. Warren et al.

Closing Plenary Lunch: Summing Up. S. T. Michaletz

SOCIETY SECTION AND CHAPTER NEWS

Canada Chapter Newsletter

Southeastern Chapter Newsletter

MEETINGS

Meeting Calendar

International Biogeography Society. Tenerife, Canary Islands.

Evolutionary Change in Human-altered Environments. Institute of the Environment. University of California, Los Angeles, California

The BULLETIN OF THE ECOLOGICAL

SOCIETY OF AMERICA (ISSN 0012-9623)

is published quarterly by the

Ecological Society of America, 1707 H Street, N.W., Suite 400, Washington, DC

20006.

It is available online only, free of charge, at ‹http://www.esapubs.org/bulletin/current/current.htm›.

Issues published prior to January 2004 are available through

‹http://www.esapubs.org/esapubs/journals/bulletin_main.htm›

Bulletin

of the Ecological Society of America, 1707 H Street, NW, Washington DC 20006

Phone (403) 220-7635, Fax (403) 289-9311,

E-mail: [email protected]

Associate

Editor Section

Editor, Ecology 101 |

Section

Editors, |

The

Ecological Society of America

GOVERNING BOARD FOR 2006–2007

President: Alan Covich, Institute of Ecology, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602

President-Elect: Norm Christensen, Nicholas School of the Environment and Earth Sciences, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708

Past-President: Nancy B. Grimm, School of Life Sciences, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287-4501

Vice President for Science: Gus R. Shaver, The Ecosystems Center, Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, MA 02543

Vice President for Finance: William J. Parton, Natural Resource Ecology Laboratory, Colorado State University, Ft. Collins, CO 80523-1499

Vice President for Public Affairs: Richard V. Pouyat, 3315 Hudson St., Baltimore, MD 21224

Vice President for Education and Human Resources: Margaret D. Lowman, Biology and Environmental Studies, New College of Florida, Sarasota, FL 34243-2109

Secretary: David W. Inouye, Department of Biology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742-4415

Member-at-Large: Dennis Ojima, Natural Resource Ecology Laboratory, Colorado State University, Ft. Collins, CO 80523-1499

Member-at-Large: Jayne Belnap, USGS Cayonlands Field Station, Southwest Biological Science Center, Moab, UT 84532

Member-at-Large: Juan J. Armesto, Departmento de Biologia, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile

AIMS

The Ecological Society of

America was founded in 1915 for the purpose of unifying the sciences of

ecology, stimulating research in all aspects of the discipline, encouraging

communication among ecologists, and promoting the responsible application

of ecological data and principles to the solution of environmental problems.

Ecology is the scientific discipline that is concerned with the relationships

between organisms and their past, present, and future environments. These

relationships include physiological responses of individuals, structure

and dynamics of populations, interactions among species, organization

of biological communities, and processing of energy and matter in ecosystems.

| Regular member: | Income level | Dues |

| <$40,000 | $50.00 | |

| $40,000—60,000 | $75.00 | |

| >$60,000 | $95.00 | |

|

Student member:

|

$25.00 | |

| Emeritus member: | Free | |

|

Life

member:

|

Contact Member and Subscriber Services (see below) |

Ecological

Applications $50.00 $40.00

Frontiers in Ecology Free to members

Ecological Archives Free

|

Call for Nominations: ESA AwardsThe Awards Committee of the Ecological Society of America solicits and encourages nominations from members of the ESA for each of the awards listed below. ESA especially encourages nominations of candidates from traditionally underrepresented groups, including women and minorities. In preparing a nomination, it would be helpful to consult with the Chair of the specific award subcommittee or the Awards Committee Chair. More information about the process is available on ESA’s web page ‹http://www.esa.org› under ESA Awards. Nomination schedule To be given full consideration, nominations for awards should be completed by 30 November 2006. They should be submitted directly to Chairs of the specific award subcommittees (e-mail addresses below). Eminent Ecologist Award The Eminent Ecologist Award is given to a senior ecologist in recognition of an outstanding body of ecological work or of sustained ecological contributions of extraordinary merit. Nominees may be from any country and need not be ESA members. Recipients receive lifetime active membership in the Society. Recent recipients include Richard Root, Sam McNaughton, Lawrence Slobodkin, and Daniel Simberloff. To submit a nomination, contact Paul Dayton, Chair, Eminent Ecologist Award Subcommittee ‹[email protected]›. Odum Education Award The Eugene P. Odum Award recognizes an ecologist for outstanding work in ecology education. This award was generously endowed by, and named for, the distinguished ecologist Eugene P. Odum. Through teaching, outreach, and mentoring activities, recipients of this award have demonstrated their ability to relate basic ecological principles to human affairs. Nominations recognizing achievements in education at the university, K–12, and public levels are all encouraged. Recent recipients include Richard Root, James Porter, and Claudia Lewis. To submit a nomination, contact Charlene d’Avanzo, Chair, ESA Odum Education Award Subcommittee ‹[email protected]›. Honorary Member Award Honorary Membership in the Society is given to a distinguished ecologist who has made exceptional contributions to ecology and whose principal residence and site of ecological research are outside of North America. Up to three awards may be made in any one year until a total of 20 is reached. Nominations of women and minority candidates, as well as those from developing countries, are especially encouraged. Recent honorees include Madhav Gadgil, Carlos Herrera, Erkki Haukioja, and Suzanne Milton. To submit a nomination, contact Sandra Tartowski, Chair, Honorary Member Award Subcommittee ‹[email protected]›. George Mercer Award The Mercer Award is given for an outstanding ecological research paper published by a younger researcher (the lead author must be 40 years of age or younger at the time of publication). If the award is given for a paper with multiple authors, all authors will receive a plaque, and those 40 years of age or younger at the time of publication will share the monetary prize. The paper must have been published in 2006 or 2007 to be eligible for the 2007 award. Nominees may be from any country and need not be ESA members. Recent recipients include Jean L. Richardson, John Stachowitz, Daniel Bolnick, and Anurag Agrawal. Nominations should be sent to Alan Hastings, Acting Chair, Mercer Award Subcommittee ‹[email protected]›. W. S. Cooper Award The W. S. Cooper Award is given to honor an outstanding contributor to the fields of geobotany and/or physiographic ecology, the fields in which W. S. Cooper worked. This award is for a single contribution in a scientific publication (single or multiple authored). Nominees need not be ESA members and can be of any nationality. Recent recipients include Jack Williams and coauthors, Daniel Gavin and coauthors, and Stephen Hubbell.. Nominations should be sent to Miles Silman, Chair, Cooper Award Subcommittee ‹[email protected]›. Distinguished Service Citation The Distinguished Service Citation is given to recognize long and distinguished service to the ESA, to the larger scientific community, and to the larger purpose of ecology in the public welfare. Recent recipients are Jim Reichman, Jim MacMahon, and Margaret Palmer. To submit a nomination, contact Paul Dayton, Chair, Distinguished Service Citation Subcommittee ‹[email protected]›. Sustainability Science Award The Sustainability Science Award is given to the authors of a scholarly work that makes the greatest contribution to the emerging science of ecosystem and regional sustainability through the integration of ecological and social sciences. One of the most pressing challenges facing humanity is the sustainability of important ecological, social, and cultural processes in the face of changes in the forces that shape ecosystems and regions. This ESA award is for a single scholarly contribution (book, book chapter, or peer-reviewed journal article) published in the last 5 years. Nominees need not be ESA members and can be of any age, nationality, or place of residence. Recent recipients are Marten Scheffer and colleagues, Thomas Dietz and colleagues, and the Millenium Assessment Team. To submit a nomination, please contact Garry Peterson, Chair of the Sustainability Science Award Subcommittee ‹[email protected]›. Corporate Award The Corporate Award is given to recognize a corporation, business, division, program, or an individual of a company for accomplishments in incorporating sound ecological concepts, knowledge, and practices into planning and operating procedures. This award was designed to encourage use of ecological concepts in business and private industry and to enhance communication among ecologists in the private sector. Educational institutions and government agencies are not eligible for this award. Recent recipients of the Corporate Award include Norm Thompson Outfitters, Taylor Guitars, Bon Appétit Management Company, and the Straus Family Dairy. The award can be made each year in any one of the following six categories: A) Environmental Education: Organizations producing educational materials in print, film, video, software, or multimedia formats; conducting workshops or training sessions; or providing other types of educational products or services that are primarily concerned with environmental education. B) Stewardship of Land Resources: Organizations concerned with the use of land resources, land‑use planning, multiple use of land resources, resource extraction, land development, and related activities. C) Resource Recycling: Organizations concerned with the recovery, reclamation, or recycling of natural resources such as wood and paper products, glass, metals, waste water, and related residuals. D) Amelioration of Risks from Hazardous and Toxic Substances: Organizations concerned with the safe manufacturing, distribution, and use of hazardous and toxic substances, those concerned with the identification and reduction of risks, as well as those in mitigative and restorative activities. E) Sustainability of Biological Resources in Terrestrial Environments: Organizations concerned with forestry, wildlife management, range management, and agroecosystems, including areas such as soil conservation, integrated pest management, fertilization, irrigation, hybridization, and genetic engineering. F) Sustainability of Biological Resources in Aquatic Environments: Organizations concerned with aquaculture and commercial fishing, including shellfishing and related industries; sports fishing, boating, and related recreational uses; lake management and restoration; wetlands protection and restoration; channelization; dredging; and related activities. Nominations for the Corporate award may be made by industrial representatives, government officials, the general public, ESA members, or by members of the ESA Corporate Award Subcommittee. To submit a nomination or to obtain more information about the nomination procedure, please contact: Laura Huenneke, Corporate Award Subcommittee ‹[email protected]›.

|

|

Murray F. Buell Award and E. Lucy Braun Award Murray F. Buell had a long and distinguished record of service and accomplishment in the Ecological Society of America. Among other things, he ascribed great importance to the participation of students in meetings and to excellence in the presentation of papers. To honor his selfless dedication to the younger generation of ecologists, the Murray F. Buell Award for Excellence in Ecology is given to a student for the outstanding oral paper presented at the ESA Annual Meeting. E. Lucy Braun, an eminent plant ecologist and one of the charter members of the Society, studied and mapped the deciduous forest regions of eastern North America and described them in her classic book, The Deciduous Forests of Eastern North America. To honor her, the E. Lucy Braun Award for Excellence in Ecology is given to a student for the outstanding poster presentation at the ESA Annual Meeting. A candidate for these awards must be an undergraduate, a graduate student, or a recent doctorate not more than 9 months past graduation at the time of the meeting. The paper or poster must be presented as part of the program sponsored by the Ecological Society of America, but the student need not be an ESA member. To be eligible for these awards the student must be the sole or senior author of the oral paper (Note: symposium talks are ineligible) or poster. Papers and posters will be judged on the significance of ideas, creativity, quality of methodology, validity of conclusions drawn from results, and clarity of presentation. While all students are encouraged to participate, winning papers and posters typically describe fully completed projects. The students selected for these awards will be announced in the ESA Bulletin following the Annual Meeting. A certificate and a check for $500 will be presented to each recipient at the next ESA Annual Meeting. If you wish to be considered for either of these awards at the 2006 Annual Meeting, you must send the following to the Chair of the Student Awards Subcommittee: (1) the application form below, (2) a copy of your abstract, and (3) a 250-word or less description of why/how the research presented will advance the field of ecology. Because of the large number of applications for the Buell and Braun awards in recent years, applicants may be pre-screened prior to the meeting, based on the quality of the abstract and this description of the significance of their research. The application form, abstract, and research justification must be sent by mail, fax, or e-mail (e-mail is preferred; send e-mail to [email protected]) to the Chair of the Student Awards Subcommittee: Dr. Anita L. Davelos Baines, Dept. of Biology, The University of Texas-Pan American, 1201 W. University Drive, Edinburg, TX 78541-2999 USA. If you have questions, write, call (956) 380-8732, fax (956) 381-3657, or e-mail: [email protected]. You will be provided with suggestions for enhancing a paper or poster. The deadline for submission of form and abstract is 1 March 2006; applications sent after 1 March 2006 will not be considered. This submission is in addition to the regular abstract submission. Buell/Braun participants who fail to notify the B/B Chair by 1 May of withdrawal from the meeting will be ineligible, barring exceptional circumstances, for consideration in the future. Electronic versions of the Application Form are available on the ESA web site, or you can send an e-mail to [email protected] and request that an electronic version be sent to you as an attachment.

Current Mailing Address _____________________________________________________________________________ Current Telephone _________________________________________________________________________________ E-mail __________________________________________________________________________________________ College/University Affiliation ___________________________________________________________________________ Title of Presentation _________________________________________________________________________________ Presentation: Paper (Buell Award) ______ Poster (Braun Award) _______ At the time of presentation I will be (check one): I will be the sole ____ /senior ____ author (check one) of the paper/poster. Signed (electronic signatures are OK) Please attach a copy of your abstract and 250-word or less description of why/how the research presented will advance the field of ecology. |

| David Ackerly Paul Alaback Isabel Willoughby Ashton Sara Baer Nicholas A. Baer Hal Balbach Randy Balice Jennifer Baltzer Jill Baron Jayne Belnap Uta Berger Jan L. Beyers Rick Black P. Dee Boersma Kimberly Bohn Elizabeth Borer Stuart Borrett Jere Boudell Richard L. Boyce John M. Briggs Laura Broughton Thomas Bultman Willodean D.S. Burton Karen Carney Elsa Cleland Dean Cocking Beverly Collins Scott Collins Jamie Cromartie Todd A. Crowl Patrick Crumrine Charlene D’Avanzo Fran Day Justin Derner Diane DeSteven Martin Dovciak Michael Drescher Andy Dyer |

Vince Eckhart Jenny Edwards Louise Egerton- Warburton S.K. Morgan Ernest Gary Ervin Todd Esque Stan Faeth Joseph Fail Kenneth J. Feeley Ann-Marie Fortuna Jeremy Fox Janet Franklin Tadashi Fukami Hazel Gordon Louis J. Gross Daniel S. Gruner Robert O. Hall Jonathan Halvorson Stephanie Hampton Charles P. Hawkins Scott A. Heckathorn Brent Helliker Jeff Herrick Ben Holcomb Ricardo Holdo David Holway Claus Holzapfel David Humphrey Gary R Huxel Chris Ivey Pierre-Andre Jacinthe Mara Johnson Derek Johnson Shibu Jose Alan K. Knapp Troy A. Ladine Mimi E. Lam Tracy Langkilde |

Erin Lehmer Xuyong Li Orie Loucks Sarah Lovell Barney Luttbeg Daniel Magoulick Kumar P. Mainali Vikas Malik Steven Matzner Sasmita Mishra Randy Mitchell Kiyoko Miyanishi Jack Morgan Sherri Morris Rebecca Mueller Christa Mulder Vince Nabholz Elizabeth Newell Nancy Eyster-Smith Asko Noormets Erin O’Brien Kiona Ogle Dennis Ojima Robert A. Olexsey Wendy Palen Chris Paradise Chris Picone Jose Miguel Ponciano Evan Preisser S. Raghu Uwe Rascher Jennifer Rehage Jessica E. Rettig Jennifer Rhode Paul Ringold Jennifer Rudgers Carl R. Ruetz Christopher F. Sacchi Cindy Sagers |

Cindy Salo Sam Scheiner Paul Schmalzer Stefan Schnitzer Eugene Schupp Jen Schweitzer Eric Seabloom Anna Sher Colleen Sinclair Doug Slack Dave Smart Peter C. Smiley Melinda D. Smith Robin Snyder M.A. Sobrado Jed Sparks Martin Henry H. Stevens Andrew Storfer Deanna Stouder Sharon Y. Strauss Conrad Toepfer Chris Tripler Amy Uhrin Astrid Volder Kevina Vulinec Linda Wallace Yong Wang Nicole Welch William E. Williams Susan Will-Wolf Herb Wilson Rachael Winfree Scott Wissinger Stan Wullschleger Ruth Yanai Bai Yang |

NSF Student Travel AwardsNational Science Foundation’s Research Experiences for Undergraduates Program Dr. Val Smith provided Undergraduate Mixer attendees with an overview of the National Science Foundation’s Research Experiences for Undergraduates program, which encourages and funds research opportunities for undergraduates in the areas of ecology and evolutionary biology. The 13 participants at the 2006 ESA Annual Meeting were supported by $1000 ESA/REU travel awards made possible by his grant from NSF ‹http://www.esa.org/memphis/REUAwards.php› Dr. Smith will make available more than 20 additional ESA/REU travel awards for the next Annual Meeting in San Jose, California, in August 2007, and further details about these competitive travel awards will be available on the San Jose Meeting web site later this year. ESA members are very strongly encouraged to alert qualified undergraduates to apply for these exceptional awards! All applicants for ESA/REU travel awards must have performed their undergraduate research either through an REU Site, or through an REU supplement to a regular NSF grant. Please look for and click on the special new “Students” button, which will be added to next year’s web page! Val H. Smith |

Resolution of RespectProfessor Syunro Utida (1913–2005)On 2 November 2005, Syunro Utida, honorary member of the Ecological Society of America, died at the age of 92 after a long illness. He was an unusual ecologist who applied elegant laboratory experiments to elucidate ecological principles. He was born 5 July 1913 in Gifu Prefecture, Japan, as the second son of a chemist, Tokiji Utida, in the delta area where the Kiso, Nagara, and Ibi Rivers join. Each village is surrounded by dikes to protect it from high tides, and also from flooding by the rivers. Prof. Utida chose entomology as his major, although he once mentioned that he had originally wanted to be an archaeologist. He graduated from Kyoto Imperial University in 1936, and entered the Graduate School of Kyoto Imperial University. During his undergraduate period he was taught by Prof. Hachiro Yuasa. Prof. Yuasa, the founding professor of the Entomological Laboratory of Kyoto Imperial University, went to the USA when he was young, and was educated at Kansas State Agricultural College, and the University of Illinois, where he obtained his Ph.D in Entomology. He was famous as a liberalist, and his guidance reflected his idealism. Dr. Utida’s colleagues include K. Imanishi, the founder of Japanese primatology, and M. Morisita, known for his I index in ecology, among others. During his graduate school period, Dr. Utida was guided by Professor Chukichi Harukawa, who had also studied at the University of Illinois under Professor V. E. Shelford. Dr. Utida was strongly influenced by these two mentors. He was very independent, and he guided his students to be independent in their research. During his lifetime, he published 120 scientific papers, among which only 19 are coauthored. Following the example of Prof. Yuasa, he never coauthored the papers that his students wrote, although he constantly gave suggestions and guidance during the research and manuscript preparation phase. His teaching policy was to carefully avoid providing excessively close supervision. He strongly believed that the whole responsibility of any research lies in the hand of those who conducted the research. Despite all his accomplishments, Dr. Utida was an unassuming and gentle man. However, behind his amicable smile, he had a firm faith in the importance of rigorous experimental research. This belief later brought unfortunate incidents. In 1939, he presented his work on the density effect and equilibrium at the Japanese Entomological Society. This was his debut presentation at a scientific meeting. It was well received and commended by colleagues. He was forced to treat them to tea and cake. But he later wrote in his memoir that the presentation was more valuable than the cost of the treat. The presentation was a part of his dissertation research, which was later published in a series of nine papers in the Memoirs of the College of Agronomy, Kyoto Imperial University, from 1941 to 1943. It was a comprehensive work on density effects on the dynamics of animal populations, illustrated by experimental work with the adzuki bean weevil (Callosobruchus chinensis). It is rather amazing, considering Japanese–United States relationships and poor communications at that time, that his work was extensively cited as early as 1949 in the now classic ecology textbook, Principles of Animal Ecology, by Allee et al. (1949). In 1948 he became the professor of Entomology at Kyoto University, succeeding Professor Harukawa, a post he held for 30 years until his retirement in 1977. Soon after the end of the Second World War, his interest extended to the dynamics of hosts and parasitoid wasps, using the bean weevils and their larval parasitic wasps as subjects. He published his experimental results in the journal Ecology in a series of papers from 1950 to 1957. In 1957 he was invited to the Cold Spring Harbor Symposium on Quantitative Biology. After that time, his work on host and parasitoid dynamics was known worldwide. His work was extensively cited in several ecology textbooks published in the early 1970s, (e.g., Krebs 1972, Colinvaux 1973, Ricklefs 1973). His work on host and parasitoid dynamics is now a classic in ecology, and even recent textbooks cite his work (e.g., Begon et al. 1996). Because of his exceptional contribution to ecological science, he was elected an honorary member of the British Ecological Society, and was also awarded honorary membership by the Ecological Society of America in 1992. In addition, he was made an honorary member of the Society of Population Ecology, Japanese Society of Ecology, and Japanese Society of Applied Entomology and Zoology. His research on host–parasitoid dynamics ended abruptly after a successful presentation at the International Congress of Entomology in Vienna, Austria in 1961. At that time, he was planning to extend the scope of his experiments, first by increasing the number of bean weevil species to more than two, and then increasing the number of species of parasitic wasps. He already had the candidate organisms in hand. He had demonstrated experimentally that the two bean weevil species (C. chinensis, and the cowpea weevil, C. maculatus) could not coexist in a small Petri dish for long, but introduction of parasitic wasp species made it possible for the two bean weevil species to coexist. In his experiments, the interspecific competition always ended in the extinction of C. chinensis. However, when another researcher later repeated the same experiment with the same materials, he obtained the reverse result, namely, the extinction of C. maculatus. Dr. Utida also repeated the experiment, resulting in the extinction of C. maculatus. He could not comprehend the results, and his own confidence in his entire set of experiments was greatly shaken. He unfortunately abandoned all future experiments on that subject. If he had continued, the plan was obviously very far advanced for that period, and he would have performed pioneering work on the stability–complexity relationship in biotic communities. We had to wait until his students began experimental studies using similar materials along the lines he planned to understand the problem he encountered. The strain of C. maculatus Dr. Utida used was established from a specimen accidentally imported with beans sent by the U.S. government as food aid just after the war. When he began rearing C. maculatus, many of the adults were of an odd active form, but over many generations, the adults increasingly were of the normal form. It seems very likely that some change in ecological character(s) in C. maculatus occurred during the laboratory breeding, especially in the early period just after their introduction to laboratory conditions. It also turned out that the interactions of these two bean weevil species were very delicate. When four geographical strains of each species were employed, the interspecific competition resulted in the extinction of C. maculatus in 10 combinations out of 16, and the rest of the combinations ended in the extinction of C. chinensis (Fujii 1969), similar to the experiment with Tribolium castaneum and T. confusum by Park et al. (1964). His major interest shifted to the investigation of the mechanisms of dimorphism seen in C. maculatus, which became his pet research topic; he published many papers on this topic, and continued his research even after his retirement. Although his published research was mostly confined to the dynamics of laboratory populations, he was a good naturalist, and enjoyed field study, too. In the 1950s and early 1960s, he often led a team consisting of laboratory colleagues and students to conduct field surveys on the spatial distributions of the lady beetles Henosepilachna vigintioctopunctata and H. vigintioctomaculata and the larvae of the cabbage butterfly, Pieris rapae. Several multiauthored papers were published. These papers stimulated other researchers to become aware of the importance of spatial distribution of organisms in the field, and many studies on spatial distributions of various insects followed. He was instrumental in launching the Society of Population Ecology, and kicking off the publication in 1952 of Researches on Population Ecology (now Population Ecology). It is probably the best-known ecological journal published in Japan promoting research on population ecology. In 1966 the Society of Population Ecology was launched, and Prof. Utida was elected as the first President of the Society. His last 10 years at Kyoto University were rather sad and lonely. Around 1968, campus riots prevailed in many universities in Japan by students demanding university reforms. Soon, younger faculty members joined the students, and the antagonism between professors and younger faculty and students intensified. He strongly believed in order and the integrity of research in universities, and often refused easy compromise at the collective meetings. Around that period, he always carried his resignation letter with him. Even after the turmoil subsided, his human relationships never recovered fully. After his retirement in 1977, he left Kyoto and started a new life at Hayama, near Tokyo. He once lamented that he was interested in the effect of over-crowding in his research, but ironically experienced the loneliness of under-crowding. When young scientists complained about the lack of research funds, Professor Utida often said that it was not because of the lack of money that they could not conduct good research; rather, it was because of the lack of good research that they did not get research funds. This only serves to illustrate how confident and proud he was of his scientific work. However, when he heard of plans by the state to honor him, he declined the honor, as he believed absolutely in a meritocracy. His wife, Shizuko Suga, whom he married in 1942, a devout Christian, attended her husband devotedly during his long illness. Four years before his death, he converted to Christianity. He is survived by his adored wife Shizuko, three children, six grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren. Literature cited Allee, W. C., A. E. Emerson, O. Park, T. Park, and K. P. Schmidt. 1949. Principles of animal ecology. W. B. Saunders, London, UK. Selected seminal papers by Syunro Utida Utida, S. 1941. Studies on an experimental population of the azuki bean weevil, Callosobruchus chinensis. I. The effect of population density on the progeny population. Memoirs of the College of Agriculture, Kyoto Imperial University 48:1–30. Koichi Fujii |

|

Murray F. Buell Award

The winner of the Murray F. Buell Award in 2006 is Carolyn Kurle for her paper “Introduced rats indirectly alter marine communities,” which is based on her doctoral research at the University of California, Santa Cruz under the supervision of Don Croll and Bernie Tershy. The Buell judges noted that Carolyn clearly presented the rationale for her study of the indirect effects of introduced rats on marine algal abundance in the rocky intertidal via a cross-community trophic interaction. Judges commented that the design of the study was elegantly simple, conducted on an impressive spatial scale, and that the results were surprisingly clear and convincing. One judge noted that Carolyn’s study could well become a textbook example of the concept of trophic cascades. Judges noted that Carolyn was at ease during her presentation and that she handled at least eight questions with poise, clarity, and interesting detail that showed the depth of her familiarity with this system. Judges commented that this work represents significant science that was well presented; the research was novel and successfully detailed a link between terrestrial and marine systems. In her presentation, Carolyn showed familiarity with ecological theory and with the applications of her research to conserving island ecosystems. The research showed that marine bird abundance differed on rat-infested and rat-free islands, and that this resulted in significant differences in intertidal invertebrate abundance and algal cover on the two island types. |

Her study illustrated the unexpected consequences of invasive animals and their potential to initiate indirect trophic cascades that can lead to large-scale influence on community structure. Carolyn received her M.S. from Texas A & M University in Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences in 1998, and a B.S. in Zoology and a B.A. in German Language and Literature from the University of Washington in 1994. The Buell-Braun Award Selection Committee also selected three students for Honorable Mention for the Buell Award. This recognition was given to: (1) Meghan Duffy of the University of Wisconsin at Madison for her presentation entitled “Is the enemy of my enemy really my friend? The combined effects of selective predators and virulent parasites on Daphnia populations”; (2) Volker H. W. Rudolf of the University of Virginia for his presentation entitled, “Indirect asymmetrical interactions in stage-structured predator–prey systems; cannibalism, trait-mediated interaction and trophic cascades”; and (3) Jennifer L. Williams for her presentation entitled, “An experimental approach to exotic plant success: houndstongue in its native and introduced ranges.” Christopher F. Sacchi, Buell-Braun subcommittee Chair |

|

Stephen P. Hubbell. 2001. |

|

The William S. Cooper Award is given by the Society in honor of one of the founders of modern plant ecology, in recognition of an outstanding contribution in geobotany, physiographic ecology, plant succession, or the distribution of organisms along environmental gradients. |

|

George Mercer Award Agrawal, A.A. (2004) The Mercer Award is given for an outstanding ecological research paper published by a younger researcher (the lead author must be 40 years of age or younger at the time of publication). The paper must have been published in 2004 or 2005 to be eligible for the 2005 award. Nominees may be from any country and need not be ESA members. The winner of this year’s Mercer Award is Anurag Agrawal of Cornell University, for his 2004 paper, “Resistance and susceptibility of milkweed: competition, root herbivory and plant genetic variation,” published in Ecology. A major controversy in community ecology from the middle of the last century has revolved around whether plant productivity is controlled by competition for resources or consumption by herbivores. As with many contentious dichotomies, the answer has proven to be more complex, which has demanded greater ingenuity from researchers seeking to understand the distribution and abundance of organisms. Anurag Agrawal’s Mercer Award winning paper is exemplary in the thoroughness with which it tackles this complexity. It strongly deserves recognition.

|

The experiments carefully teased apart the complex interactive effects of herbivory, plant competition, and plant genotype on milkweed performance and fitness. The non-additive effects of competition by grasses and beetle herbivory on milkweed growth was a particularly novel aspect of the results. With a quantitative genetic experiment, Agrawal showed that milkweeds growing near grass experienced more herbivory from adult Tetraopes beetles, and that this effect was directly due to beetles being attracted to grass, which serves as their oviposition site. In a manipulative experiment with beetle larvae, Agrawal also found that grass competition interacted with larval feeding on roots to negatively impact milkweed. The grass, meanwhile, enjoyed competitive release by facilitating its neighbor’s herbivore. Finally, Agrawal presented a general model to predict the conditions under which plant–plant interactions can result in net competition or facilitation via indirect effects. This paper represents the kind of holistic studies that will take our understanding of plant–herbivore interactions to a new level. Overall, Anurag Agrawal’s growing body of work, exemplified by but not restricted to this paper, is having a significant impact in the areas of plant–animal interactions and community ecology. |

|

|

The Straus Family Creamery of California has been recognized with the 2006 Corporate Award in its sustainability and land stewardship categories. This long-standing family farm has sustained a commitment to both local and landscape-scale stewardship of resources within a region of rapid change and enormous social pressures. Bill Straus founded the dairy in 1941, sixty miles north of San Francisco. In the years after, Bill and Ellen Straus participated actively in the Marin Conservation League, the efforts to preserve the national seashore, and the creation of the Marin Agricultural Land Trust (MALT) in 1980. The latter organization has enabled the preservation of working agricultural landscapes in the face of intense pressures for development.

In the second generation, Albert Straus (son of Bill and Ellen) converted the farm to organic operation. Albert credits the conversion to organic with preserving the farm as an economic success, while neighboring conventional dairies have been fading away. Beyond typical organic practices, Albert has been applying innovative technology in every aspect of dairy and farm operations. The Straus Family Creamery now creates electricity from a methane Straus digester. The digester captures naturally occurring gas from manure and converts it into electricity. With this new system, Straus expects to generate up to 600,000 kWh per year, saving about $6,000 in monthly energy costs. This process also eliminates methane, a natural by-product of manure. The Straus generation is connected to the local electrical grid, allowing them to run their meter “backwards” and contribute to the regional power supply. Finally, the farm has now converted a diesel back-up generator to run on straight vegetable oil, and is in the process of converting farm vehicles to vegetable oil as well. Finally, the creamery washes its glass milk bottles with a less toxic method than the typical one. The Ecological Society of America is delighted to recognize this second-generation family farm for its sustained commitment to sound agricultural practice, technological innovation in reducing environmental impact, and contributions to regional-scale conservation of working landscapes. |

|

|

Daniel Simberloff is not only eminent in ecology today: for many years, he has been the quintessential ecological iconoclast.

Any undergraduate student who has ever had an ecology class is familiar with Dan Simberloff’s work. His experimental island biogeography papers with E.O. Wilson are textbook classics, elegant experimental studies that appeared to beautifully confirm the emerging theory of island biogeography. Simberloff rigorously tested a nascent body of theory, which won him the Mercer Award with Wilson in 1971. If he had done nothing else, this work would have assured him lasting prominence. But many ecologists were dismayed by his 1976 Science paper, in which he threw stones at his own glass house, arguing that most of the insect turnover in this assemblage was ephemeral and did not therefore confirm the predictions of the theory. Few ecologists among us have the courage to publicly challenge our own paradigm in this way, particularly once it has become widely accepted. As society began to embrace island biogeography and extend it to designing nature reserves, Simberloff was further cast as a bete noire when he argued (backed by plenty of empirical data) that large reserves are not always the best conservation option. |

His more recent work has been equally notorious. He has written pointed and controversial critiques about the wisdom of biological control, calling attention to the threats imposed by invasive species and raising the specter of “invasional meltdown.” His criticisms of biological control gone bad (and his data to support those criticisms) are slowly reaching land managers and the general public. He has become a world expert on the threats imposed by invasive species. |

|

I. REPORTS OF THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR AND STAFF

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR ESA has had another productive and successful year. The upward trend in membership continues, with growth to 10 000 clearly in sight. Our finances are strong and we are building a reserve to allow us to operate with no loss of service to our members in the event of some unforeseen disruption. The Annual Meeting in Montreal produced a record attendance and our new Annual Meeting staff team has developed a number of initiatives that will begin in Memphis. Our themed meeting in Mexico this year was an exceptional success. The program attracted participants from all over the world, and travel support enabled many students from Latin America to attend. While in Mexico, ESA hosted a meeting of the Federation of the Americas, a gathering of Presidents of ecological societies from the Americas, led by ESA. The Federation activities are expanding, as is its membership. In addition to fundraising and supporting the Mexico meeting, Science programs included leadership in a collaborative effort with other scientific societies on data-sharing issues, a successful National Agricultural Air Quality Workshop, bringing together attendees from 25 countries, and a continued focus on sustainability science. A major new initiative in 2005 was the establishment of a Development Office to guide us in pursuing funding opportunities for priority activities identified by the Governing Board and staff. One of these is the plan for a Knowledge Partnership in the Southeast Region, an effort to address issues identified by stakeholders in the region. Our Society’s journals continue to be among the best in the field. Our newest publication, Frontiers, moved up in the ISI rankings (2nd out of 134 in the Environmental Science category and 6th out of 112 in the Ecology group) and Ecology, Ecological Applications, and Ecological Monographs remain top-rated journals. In 2005 we inaugurated the ESA data registry, a repository for authors to make their data widely available. This year, as well, we provided all our institutional subscribers with print and online access to our journals at a reduced cost. Rapid Response Teams, established last year, are thriving. Members involved have provided scientific input on congressional legislation, proposed rule-making by the Administration, and to a “friend of the court” brief submitted to the Supreme Court. ESA’s policy briefings, leadership in national coalitions, numerous fact sheets, position papers, official ESA statements, and media outreach build ESA’s reputation in the policy arena. ESA’s SEEDS program generates excitement among participants and ESA members involved in the program. The program hosted students at both the Montreal meeting and the Mexico meeting. SEEDS students attended a field trip to the Sevilleta Long Term Ecological Research Project, and another to sites in Kansas. For the first time this year, a leadership workshop was held that included three generations of SEEDS fellowship students. The following staff reports highlight these accomplishments—and many more. ESA is a strong and growing organization of which I am proud to be Executive Director. Our staff team is professional, dedicated to the mission of the Society, and to serving the membership. All of us are enthusiastic about the future of ESA and our role in its success. Submitted by: |

FINANCES/ MEMBERSHIP/ ADMINISTRATION

ESA continues to grow! The number of ESA members grew from 8718 in 2004 to 9264 members in 2005, and we have already passed that figure for 2006. We expect to end our 2006 membership year with close to 10,000 members. We anticipate ending the 2005–2006 fiscal year with a positive bottom line. The meeting in Montreal was well attended, library subscriptions are holding up despite budget problems for many institutions, and expenses have been kept within normal variances. Membership and subscriptions for the calendar year 2005 were: Total Membership: 9264 By Class: Regular: 6188 Subscriptions: Ecology total: 5806 Ecological Applications total: 3374 Ecological Monographs total: 2823 Chapter Membership: Canadian: 144 Section Membership Asian: 94 Membership affliation: Academic: 66% Ethnicity: White: 75% Gender: Male: 60% Administrative staff: |

| ANNUAL MEETING

ESA’s 90th Annual Meeting was held in Montreal, and was ESA’s largest meeting to date, with close to 4500 attendees. This was a joint meeting with INTECOL, and program chairs from both societies worked closely with ESA staff. Challenges for staff included working with French-speaking vendors, paying hundreds of thousand of dollars worth of expenses in a foreign currency, and coping with customs, NAFTA, and immigration issues. However, all were overcome and we had a successful meeting. Upon returning from Montreal, work immediately began on the 91st Annual Meeting, held in Memphis, Tennessee. A smooth transition was made from former Meeting Manager Ellen Cardwell, who left the Society in September 2005, to Michelle Horton, who came on board as Meeting Manager in October 2005. In addition, the Program Assistant position has been filled by Devon Rothschild, who is a full-time ESA staff member. Program Chair Kiyoko Miyanishi and Local Host Chair Scott Franklin have worked closely with ESA staff in the planning of the Memphis Annual Meeting. We had ~2200 abstracts submitted, which leads us to expect roughly 3000 attendees. We continue to work on new programs to “green” the meeting. We have continued the effort begun in Montreal to encourage attendees to make donations to outside organizations to offset their carbon usage. We have begun a new program encouraging attendees to re-use the meeting tote bags. A new meeting patch will be given each year to those bringing back their bags from prior years. This will be the first year we are completely paperless with regard to the Abstracts, the end of a 3-year transition from printed Abstract books to electronic-only access. The Abstracts are available online through the itinerary planner, will be given to all attendees as a CD, and are available throughout the convention center at Abstract kiosks. Work has also begun on the 92nd Annual Meeting, which will be held in San Jose in August 2007, and will be a joint meeting with the Society for Ecological Restoration International. A call for proposals has been sent to the membership. We have contracted with a new vendor to provide abstract submission software. Program chair Kerry Woods has been working with ESA staff and Memphis Program Chair Kiyoko Miyanishi. Rachael O’Malley will be the Local Host. Future meetings 92nd Annual Meeting—San Jose, California—5–10 August 2007 93rd. Annual Meeting—Milwaukee, Wisconsin—3–8 August 2008 Annual Meeting staff: Elizabeth Biggs, CFO, Director of Administration; Michelle Horton, Meeting Manager, Tricia Crocker, Meeting Associate and Registrar; Devon Rothschild, Program Assistant |

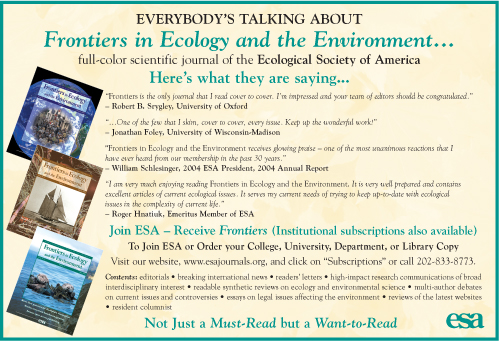

| FRONTIERS IN ECOLOGY AND THE ENVIRONMENT

Frontiers is now in its fourth year of publication, and has established itself as one of the top-ranked journals in the field of ecology and environmental science, while still maintaining a reputation for readability and accessibility. Impact factor In June 2006, Frontiers received its second impact factor ranking. The journal is ranked 2nd out of 134 journals in the Environmental Science category, and 6th out of 112 journals in the Ecology category. Frontiers in China In November 2005, an agreement was signed between the Chinese Government and ESA, providing online access to all ESA journals, including Frontiers, for up to 800 institutional libraries in China. This agreement was organized in conjunction with Charlesworth China, a company that specializes in introducing western scientific journals to the Chinese market. Special Issues The Frontiers Special Issue on China is complete and will be published in September 2006. This issue, made up entirely of articles written by Chinese authors in China, will focus on air and water pollution, urbanization, biodiversity loss, and land-use change. Although the abstract of each article appears in both English and Chinese in the journal, efforts are underway to find the necessary funding to have the entire issue translated into Chinese, as was done with the February 2005 Special Issue: Visions For An Ecologically Sustainable Future. Copies of this issue will be distributed free in China, by the authors and at EcoSummit 2007. Ecological Complexity and Sustainability: Challenges and Opportunities for 21st Century’s Ecology (Beijing, China, May 2007) where the ESA will have a booth. A further Special Issue is also in preparation, based on the ESA meeting held in Merida, Mexico, in January 2006 (Ecology in an Era of Globalization). This issue, which is supported by a grant from the NSF, is scheduled to appear late in 2006 or early 2007. The issue will include an editorial by Jonathan Lash, Director of the World Resources Institute; an introductory article by co-chairs Jeff Herrick (USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, New Mexico) and Jose Sarukhan (Instituto de Ecología-UNAM, Mexico; three review articles, based on the three themes of the meeting: Invasive species, Production, and Migration; and the six best workshop “reports,” written by the chairs of workshops at the Merida meeting. All the other workshop reports submitted will be published online. All contents have been peer reviewed. Paper Award In October 2006, Frontiers won the Bronze Award in the Aveda Environmental Awards for Best Practices in Environmental Sustainability. The journal tied for third place with the Nature Conservancy magazine. The gold award was won by the magazine Natural Health. Articles Articles received as of 14 July 2006 Conferences In the past 12 months, Frontiers staff have attended a variety of meetings, including the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry Annual Meeting (Baltimore, Maryland), the ESA meeting, Ecology in an Era Of Globalization (Merida, Mexico), the AAAS Annual Meeting (St Louis, Missouri), the 2006 Ocean Sciences meeting (Honolulu, Hawaii), the Council of Science Editors Annual Meeting (Tampa, Florida), and the Society for Scholarly Publishing Annual Meeting (Washington, D.C.). Finances During the course of 2005, Executive Director McCarter and Frontiers Editor-in-Chief Silver visited a number of federal agencies, looking for interim financial support for the journal, while institutional subscription and advertising revenue continues to build up. The following agencies generously contributed funds: NOAA: $45 000 Submitted by: Sue Silver |

| DEVELOPMENT OFFICE

Fran Day joined the staff of the Ecological Society of America on 6 February 2006. With the assistance of ESA staff and the Development Committee, the initial draft of the development master plan was completed in March 2006. Since that time it has been continuously revised and updated as we completed research and/or developed proposals. We have focused on priorities as determined by the Governing Board. They include: Education Programs; Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment; Knowledge Partnerships; Federation of the Ecological Societies of the Americas; and Science Office programs. Case statements and funding strategies have or are being developed for each of the above. Education programs Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment The funding strategy for Frontiers is to focus on the development of additional revenue through sponsorships, increased advertising, and grants development. The marketing package for Frontiers is in the design and materials development phase. We have identified and ranked potential sponsors and advertisers and developed the marketing plan. The first phase of the sponsorship marketing plan will begin in September 2006. We are identifying potential grantors and underwriters for planned special issues of the journal, as well as institutional support. We will e-mail a voluntary consumer survey to the membership to provide information that will support the development of sponsorships. Knowledge Partnerships The inaugural focus of the Knowledge Partnerships is the Southeast region. We have identified a list of potential funders, and in collaboration with the Planning Committee chaired by Alan Covich, we are developing a case statement to provide to potential funders. The Federation of the Ecological Societies of the Americas The case statement for the Federation has been developed and sent to four potential funders. Two additional proposals are in development. Science Office Programs We have assisted with the development of a symposium presented by ESA members at the annual Society for Human Ecology in Bar Harbor, Maine, 18–21 October 2006. We have also helped with the development of a case statement for the Nitrogen 2007 Conference and begun discussions with the Golf Course Superintendent’s Association of America regarding potential support. Annual Fund for the Millennium The plan for the Millennium Fund calls for a campaign of two e-mails and one regular mail contact over the next nine months. The first e-mail was sent in late June and we are receiving and tracking contributions. The purpose of this particular campaign is to increase the number of donors. At the time of this report, we have received 17 contributions. The second e-mail will be sent in the second week of November 2006. A mail appeal will be included with the Annual Report. In addition, we have created a promotion for the Annual Meeting called “Growing Ecology” and these responses will be tracked carefully. Membership Development Test Campaign The membership test campaign is well underway: the lists to be tested have been identified, the materials are in production, and the tracking system is established. The first test package will be mailed to 5000 potential members in September 2006. Other development activities include Building the Prospect and Donor Base—we have identified over 300 potential major donors and entered ~100 into the database. We have also assisted with the development of the Conflict-of-Interest Policy and the Guidelines for Identifying Corporate Donors. Submitted by: Fran Day |

| PUBLIC AFFAIRS OFFICE

Public Affairs Over the past year, ESA public affairs activities focused on conveying ecological information and resources to the media and to Congress, working with the broad scientific community to foster support for science, publicizing the Society’s activities, and outreach to ESA members. Highlights 1) This year, ESA’s Rapid Response Teams provided timely scientific input to all three Branches of Government, providing expertise on congressional legislation, proposed rule changes from the Administration, and to the Supreme Court. 2) Working with Society President Nancy Grimm, Public Affairs staff developed and distributed 10 letters from the Society. 3) ESA sponsored or cosponsored four public briefings on issues ranging from forest fires to hurricanes. 4) Members and staff met with targeted congressional and Executive Branch offices to discuss issues of concern to the ecological community. 5) The Office assisted members of the media weekly with stories ranging from climate change to National Park Service science. Environmental policy Thanks to ESA member experts, Society leaders, and ESA Policy Analyst Laura Lipps, the Society was able to again play an active role in numerous environmental policy issues over the last year. • Members of the Society’s Rapid Response Teams (RRTs) provided ESA expertise to an Amicus brief (“Friend of the Court”) submitted to the Supreme Court. The Court heard arguments on several wetlands case in early 2006. Other societies joining ESA in filing the Brief were the Society of Wetland Scientists, American Society of Limnology and Oceanography, and the Estuarine Research Federation. ESA President Nancy Grimm, President-Elect Alan Covich, and VP for Public Affairs Richard Pouyat reviewed and approved the brief, which was prepared by the Southern Environmental Law Center on the societies’ behalf. (The brief has been printed in full in the ESA Bulletin 87(2):132–154.) • RRT members David Lodge, Susan Williams, and Richard Mack, all authors of the Society’s invasive species position paper, presented the paper in a National Press Club briefing and met with targeted Hill staffers to discuss its policy implications. • Working with ESA’s President Nancy Grimm and with RRT members, PAO developed and distributed 10 ESA statements throughout the year, which addressed a wide range of issues including a proposed rule on stream mitigation, ocean research, Great Lakes Implementation Act, and the Administration’s American Competitiveness Initiative. • ESA RRT members helped develop a multisociety position statement on the Endangered Species Act, subsequently released as part of a Senate-side briefing. • RRT members Stan Temple (UW-Madison), and Virginia Dale (Oak Ridge National Laboratory), participated in a 2-hour working meeting on Endangered Species Act reform legislation with Senator Chafee’s office. Chafee’s staff person has subsequently followed up several times with the scientists. • ESA RRTs also provided input on science education incentives, federal fisheries science, and climate change. Science appropriations • Nadine Lymn, Director of Public Affairs, continued to co-chair the Biological Ecological Sciences Coalition (BESC), working to raise awareness in the White House and Congress about the state of funding for the nonmedical biological sciences. • As part of a BESC event, ESA President Nancy Grimm and Lymn met with two majority staff directors and other professional staff of the House Science Committee, as well as with Representative Ehlers’ (R-MI) office in early December. Discussions centered on how to advance the life sciences in a political climate focused on economic competitiveness. In addition, Lymn and other BESC colleagues requested that Members of Congress avoid making public comments that appear to pit the life sciences against the physical sciences. • ESA helped organize a Spring Congressional Visits Day for over 40 biological scientists from 22 states, including field station biologists , academic researchers , and graduate students; they participated in BESC's Spring Congressional Visits Day on 14-15 March 2006. The event included a half day of briefings from agencies, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, and from Congress. The BESC and CoFARM (Coalition for Agricultural Research Missions) evening reception honored two Members of Congress, Representatives Vernon Ehlers (R-MI) and Rush Holt (D-NJ) for their integration of research findings into environmental policies, such as the prevention and control of invasive species, and their strong support for science education. Visits on 15 March consisted of over 50 meetings with congressional offices as teams of scientists met with Members' offices to advocate for federal support of biological research. ESA’s first Graduate Student Policy Fellows as well as an RRT member participated in the events. • PAO continued to track and report on the status of legislation, federal science appropriations, and environmental policy activities in the national and international arena through its bi-weekly Policy News. In March, Lymn teamed up with staff from AIBS to write a chapter for the annual publication of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, AAAS Report: Research and Development FY 2007. The ESA/AIBS chapter analyzed the nonmedical biological science elements of the Administration’s proposed fiscal year 2007 budget. Press Throughout the year, Public Affairs Officer Annie Drinkard worked to highlight ecological research and ESA activities to the press. • Press preparations for the 2006 Annual Meeting so far have included press releases highlighting symposia and oral sessions, and working with university and agency public information officers to generate additional publicity for the meeting. • Coverage of the ESA Annual Meeting held in Montreal, Canada generated over 40 stories. Twenty reporters attended the meeting. Among the news outlets covering the conference were: CBC, Swedish Public Radio, MSNBC, Science, Nature and a host of local radio and newspapers. (ESA does not have a media clipping service; there was more coverage than we are able to track.) Some of the more popular sessions at the Society’s 90th Annual Meeting were Ecological Effects of the Chernobyl Disaster, Underneath it all (soil ecology), and Restoring the Garden of Eden (Mesopotamian marshes). • PAO staff continued to build on its media contacts this year and issued over a dozen press releases highlighting Society journal articles and the Annual Meeting. Drinkard also participated in the AAAS meeting. • ESA continued to field a steady influx of reporter-initiated calls throughout the year. Inquiries came from both the popular press (Boston Globe) and scientific (Nature) and covered a wide range of topics from science policy to hurricanes. • The media was especially interested in the cod stocks article published in Frontiers (generated 100’s of articles around the globe), the wolves’ top down effect article in Ecology (generated dozens of articles), and an Ecological Applications paper on nitrogen pollution. • Laura Lipps attended ESA's meeting in Merida, Mexico, as ESA's press representative. Proficient in Spanish, she provided meeting information to members of the seven Mexican news agencies in attendance, and arranged interviews with presenters and conference organizers. Outreach • ESA organized or co-sponsored four briefings this year: Hurricane Katrina briefing. With a congressional audience of 50, ESA Rapid Response Team (RRT) members Robert Twilley, (Louisiana State University), and Dennis Whigham (Smithsonian Environmental Research Center), briefed over 40 congressional staff on the ecology of Gulf Coast wetlands and the role of ecological science in restoring Gulf Coast ecosystems, on 26 October 2005. The scientists highlighted the role of wetlands and the importance of delta restoration, and offered recommendations on integrating ecological principles into scientific decision making in Gulf Coast recovery. ESA President Nancy Grimm opened the session, highlighting the role of ESA’s RRTs in contributing ecological expertise to environmental challenges. Invasive Species. ESA held a briefing at the National Press Club on 3 March 2006 to unveil the Society’s position paper on invasive species and their management. The event, which was moderated by ESA President-elect Alan Covich, drew an audience of 75 federal agency representatives, congressional staff, and members of the media. • Knowledge Partnerships. Following the Board’s charge to explore a possible ESA regional initiative, ESA staff, the Society’s Vice President for Public Affairs Richard Pouyat, and scientists in the Gulf Coast region met in Baton Rouge, Louisiana in December 2005. After further Board discussions, the Society is now planning to explore launching a pilot initiative that would focus on the southeast United States and address issues identified by stakeholders in that region. • ESA President Nancy Grimm and other members of the Society’s Governing Board met with NSF’s new Assistant Biology Director Jim Collins during his first week on the job. Board members also met with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Competitive Grants staff to discuss areas of mutual interest. • Lymn and Lipps, together with colleague Adrienne Sponberg (American Society of Limnology and Oceanography), developed and gave a Policy Training Workshop during the Montreal Annual Meeting which was designed to equip biological scientists with tools to participate in public policy. The trio worked with about 20 scientists to coach them in methods to influence policy, concluding with simulated congressional visits. • Drinkard and Lymn organized a special session held during the Annual Meeting designed to ease presentation jitters and offer constructive tips on public speaking. Offered since 2004, their hands-on session draws on improv’ comedy techniques. • Drinkard produced the Society’s ninth Annual Report, distributed to the membership in February. This report focused on 90 years of ESA and offered a historical quiz to test members’ knowledge of their membership Society. In addition to providing an overview of Society activities for ESA members, the report is useful for meetings with potential funding sources and with others who are interested in the Society. Public Affairs Committee Members of the Society’s Public Affairs Committee offer valuable guidance to the organization’s public affairs activities, ranging from review of newsworthy Annual Meeting abstracts to highlight to the press, and assessing pending Society position statements and papers. The Public Affairs Committee (PAC) met in late March to address several key activities planned for the Memphis meeting, including a PAC-sponsored symposium. In addition, PAC developed a new proposal for Board consideration on the development and venue of future ESA Position Papers. The Governing Board approved the new guidelines for Society public policy papers in May 2006. The committee also spent one day with the Society’s Education and Human Resources Committee, addressing areas of overlapping interest and participating in several meetings with Capitol Hill staffers. Members of the PAC are Richard Pouyat (Vice President), Rick Haeuber (Environmental Protection Agency), David Lodge (Notre Dame), Evan Notman (USFS AAAS Fellow) Candan Soykan (Student Representative), Christy Williams (USAID). Public Affairs Office staff |

| SCIENCE PROGRAMS OFFICE