Ecological Archives E096-248-A2

Alastair M. M. Baylis, Rachael A. Orben, John P. Y. Arnould, Fredrik Christiansen, Graeme C. Hays, and Iain J. Staniland. 2015. Disentangling the cause of a catastrophic population decline in a large marine mammal. Ecology 96:2834–2847. http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/14-1948.1

Appendix B. Detailed description of the age-class population matrix for the female component of the 1930s Falkland Islands southern sea lion (Otaria flavescens) population and a hypothetical Argentinean population. Also presented is the effect of commercial sealing on population size trajectories (females only) from the population model simulation.

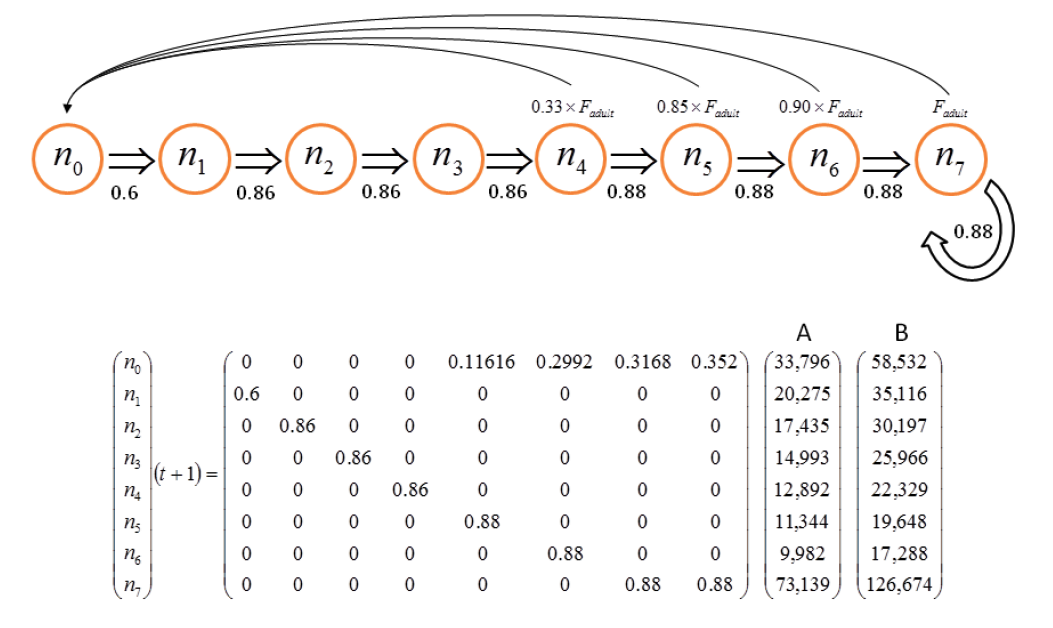

Fig. B1. Life history stages and resulting age-class population matrix for (A) the female component of the 1930s Falkland Islands southern sea lion population, following Thompson et al. (2005) and Branch and Williams (2006) and, (B) the female component of a hypothetical Argentinean population in 1936. A stationary age distribution was first obtained using Fadult = 0.352. Refer to Methods for an explanation of the values used.

Table B1. Estimated total number of southern sea lions in Argentina in 1938. Source: Godoy (1963).

Province in Argentina |

Colony |

Estimated |

Buenos Aires |

Punta Lobos |

20,000 |

Buenos Aires |

Banco Culebra |

20,000* |

Rio Negro |

Punta Bermeja |

18,000 |

Chubut |

Punta Bueno Aures |

15,000 |

Chubut |

Punta Norte |

40,000 |

Chubut |

Punta Delgada |

52,500 |

Chubut |

Punta Ninfas |

12,000 |

Chubut |

Isla Aescondida |

5,000 |

Chubut |

Isla Rasa |

105,000 |

Santa Cruz |

Bahia del Fondo |

20,000 |

Santa Cruz |

Cabo Blanco |

7,000 |

Santa Cruz |

Isla Pinguino |

52,000 |

Santa Cruz |

Loberia Oso Marino |

200,000 |

Santa Cruz |

Monte Leon |

105,000 |

Total |

671,500 |

*number of sea lions estimated in 1937

Table B2. The number of southern sea lions killed in Argentina between 1936 and 1960 (based on the number of skins produced), and used in our population model. Data was not available for individual years. To examine the effect of commercial sealing on our hypothetical Argentinean population, we therefore assumed an equal number of sea lions were killed between 1936–1940, 1941–1945, 1946–1950, 1951–1955 and 1956-1960 because only the total number of skins were reported during these 5-year periods. Source: Godoy (1963) and Thompson et al. (2005).

Year

Sea lions killed

in Argentina1936

46068

1937

46068

1938

46068

1939

46068

1940

46068

1941

30794

1942

30794

1943

30794

1944

30794

1945

30794

1946

11470

1947

11470

1948

11470

1949

11470

1950

11470

1951

2146

1952

2146

1953

2146

1954

2146

1955

2146

1956

1627

1957

1627

1958

1627

1959

1627

1960

1627

Total

460,525

Fig. B2. The effect of commercial sealing on population size trajectories (females only) from the population model simulation for (A) the Falkland Islands population of southern sea lions (1935 – 1965), and (B) a hypothetical Argentinean southern sea lion population (1936 and 1960). The colors and types of the lines correspond to the different age classes (see legend). Refer to text in Methods for an explanation of the population model and commercial sealing data used.

Literature cited

Branch, T., and T. M. Williams. 2006. Legacy of industrial whaling: could killer whales be responsible for declines in Southern Hemisphere sea lions, elephant seals and minke whales? Pages 262–278 in J. A. Estes, D. P. DeMaster, R. L. Brownell, D. F. Doak, and T. Williams, editors. Whales, Whaling and Ocean Ecosystems. University of California Press, Berkeley, California, USA.

Godoy, J. 1963. Fauna Argentina. Consejo Federal de Inversiones. Serie Evaluacibn de 10s Recursos Naturales Renovables 8 (1). Buenos Aires. Page 527 pp.

Thompson, D., I. Strange, M. Riddy, and C. Duck. 2005. The size and status of the population of southern sea lions Otaria flavescens in the Falkland Islands. Biological Conservation 121:357–367.