Ecological Archives E096-238-A1

Adam T. Ford, Jacob R. Goheen, David J. Augustine, Margaret F. Kinnaird, Timothy G. O’brien, Todd M. Palmer, Robert M. Pringle, and Rosie Woodroffe. 2015. Recovery of African wild dogs suppresses prey but does not trigger a trophic cascade. Ecology 96:2705–2714. http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/14-2056.1

Appendix A. Description of study area, methods for assessing the abundance of dik-dik and wild dogs, hypotheses tested, and statistical methods used.

Study area

We undertook our research at the Mpala Research Centre (MRC), a private wildlife conservancy in Laikipia County, Kenya (0° 17’ N, 37° 53’ E). This semi-arid savanna is characterized by a discontinuous overstory comprising about 28% of total cover and dominated by Acacia brevispica, A. etbaica, A. mellifera, Grewia sp., and Croton sp.(Young et al. 1995). MRC has a mean annual rainfall of 508 mm, varying steeply along a north-south gradient (Goheen et al. 2013) with marked inter-annual variation (Augustine 2010).

Recovery of wild dogs

Estimated biomass of wild dogs on MRC was derived from an ongoing study of > 30 packs, distributed over 12,000 km² (Woodroffe 2011). Using GPS and VHF telemetry, we quantified the movement patterns, denning periods, and composition of 9 packs at MRC since 2002. Collars were fit on 1–2 individuals in each pack. Because packs are highly cohesive, we interpreted the telemetry data from collared individuals as representative of the entire pack. To quantify the biomass density of wild dogs on MRC, we first calculated the composition of adults (ca. 23 kg) and juveniles (5-22 kg) in each pack, and summed the estimated mass of these individuals. The biomass estimate of individual juveniles was adjusted over time as they matured (Woodroffe 2011). We used telemetry to estimate the number of days that each pack spent at MRC, yielding an estimate of wild dog biomass days (in kg∙days) over the study area. We performed this calculation for the 6 months preceding each population survey for dik-dik (see below) up to January 2013, as well as in January and June of the years where surveys for dik-diks were not conducted (2003–2007). Using GPS telemetry and field observations, we identified a denning event from a single wild-dog pack comprised of 19 adults and 12 pups in 2011, during which time individuals foraged intensively within 3 km of their den (Appendix B, Fig. B1).

Monitoring the abundance of dik-dik

We monitored dik-dik abundance using line-transect sampling methods. In a previous study, one of us (DJA) performed line-transect sampling (Buckland et al. 2007) to estimate dik-dik population density along four transects (1.5–3.3 km each) in 2000 and six transects (1.5–3.3 km each) in 2001–2002 (Augustine 2010). In each survey, transects were each driven four times in 2000 and six times in 2001–2002, for a total effort of 35.9 km to 92.8 km per survey. A total of six surveys (3 in 2000, 2 in 2001, 1 in 2002) were performed prior to wild dog recovery. Beginning in June 2008 (i.e., 6 years after wild dogs had recolonized MRC) we monitored the same study area as Augustine (2010) during semi-annual surveys. Each of these surveys consisted of 20 ca. 2 km transects that were sampled once per survey, for a total effort of ca. 40 km per survey. A total of 12 surveys between June 2008 and January 2014.

Line transect sampling was always performed with two observers and one driver, from a vehicle travelling at 10 km∙h-1. Distances to animals were estimated using a laser rangefinder and bearings were estimated using a handheld compass. Density estimates and confidence intervals were calculated in Program DISTANCE using a hazard function and cosine series expansion, with observations filtered to a maximum of 72 m from the transects. We filtered data to meet the assumptions of the distance sampling (Buckland et al. 2005), resulting in the removal of 5% of dik-dik observations that were found at the farthest distances from the road.

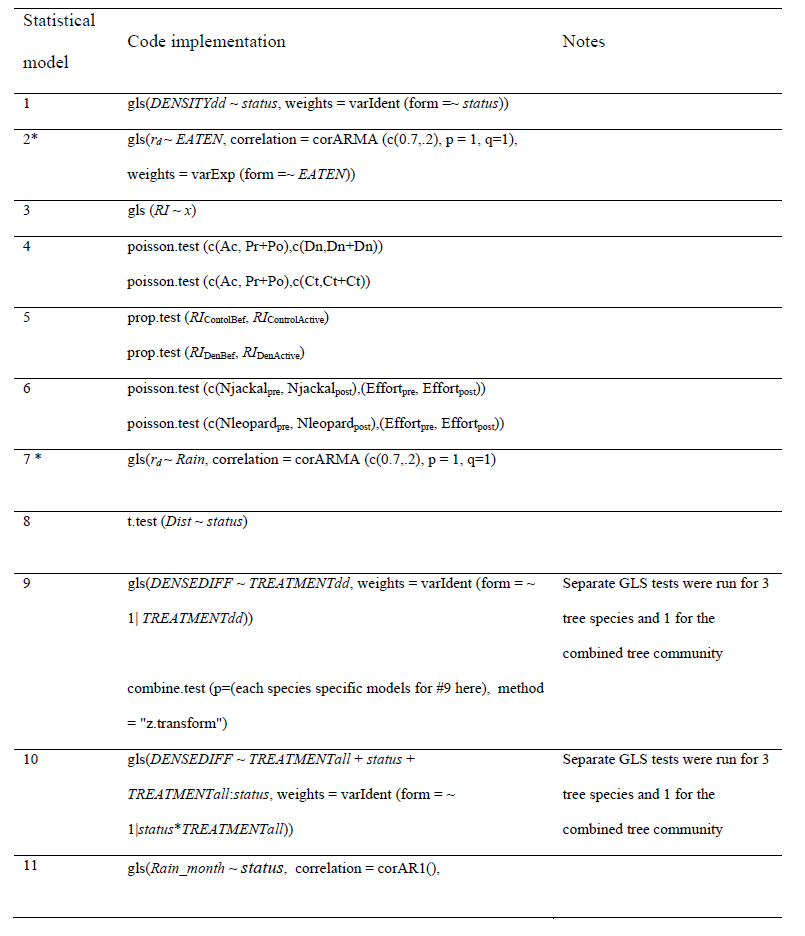

Table A1. Summary of hypotheses, predictions, and data used to evaluate the cascading effects of wild dog recovery in Laikipia, Kenya.

Hypothesis |

Description |

Prediction if trophic cascade hypothesis is correct |

Response variable |

Response variable methods or data used |

Predictor variable |

Predictor variable methods or data used |

Statistical model* |

H1 - main |

Wild dogs suppress dik-dik |

Dik-dik density is lower following wild dog recovery |

Dik-dik density pre- and post-wild dog recovery |

Distance sampling surveys (1999–2002; 2008–2013) |

Wild dog recovery status |

Telemetry and field observations of pack biomass and occupancy |

1 |

|

Wild dogs suppress dik-dik |

Wild dog biomass has a negative effect on the population growth rate of dik-dik |

Population growth rate of dik-dik |

Derived from estimates of dik-dik population density pre- and post-wild dog recovery (1999–2002; 2008–2013) |

Wild dog energetic demand (2008–2013) |

Telemetry and field observations of pack biomass and occupancy (2008–2013); diet composition of wild dogs; energy available in a dik-dik |

2 |

|

Wild dogs suppress dik-dik |

Wild dog biomass has a negative effect on dik-dik recruitment |

Recruitment index |

Derived from group sizes during distance sampling surveys (1999–2002; 2008–2013) |

Wild dog energetic demand (2008–2013) |

Telemetry and field observations of pack biomass and occupancy (2008–2013); diet composition of wild dogs; energy available in a dik-dik |

3 |

|

Wild dogs suppress dik-dik |

Proximity to a wild dog den decreases dik-dik abundance |

Encounter rate of dik-dik before, during, and after denning |

Encounter rates along road transects within and adjacent to the denning home range of wild dogs (2011–2012) |

Before vs. after wild dog denning in areas near and away from the active den site |

Telemetry and field observations of wild dog movements |

4 |

|

Wild dogs suppress dik-dik |

Proximity to a wild dog den has a negative effect on dik-dik recruitment |

Recruitment index |

Encounter rates along road transects within and adjacent to the denning home range of wild dogs (2011–2012) |

Before vs after wild dog denning in areas near and away from the active den site |

Telemetry and field observations of wild dog movements |

5 |

H1- alternatives |

Predators other than wild dogs suppress dik-dik |

Equal or less abundance of jackals and leopards post-wild dog recovery |

Relative abundance (detections per unit effort) |

Camera trapping pre- (2000–2002; 7364 trap hours at 19 sites) and post-wild dog (2011; 48513 trap hours at 97 sites) |

Wild dog recovery status |

Telemetry and field observations of pack biomass and occupancy |

6 |

|

Rainfall limits dik-dik abundance |

Equal or greater rainfall following the recovery of wild dogs |

Population growth rate of dik-dik |

Derived from estimates of dik-dik population density pre- and post-wild dog recovery (1999–2002; 2008–2013). |

Total rainfall in the 6 months preceding the dik-dik density surveys (1999–2002; 2008–2013) |

Rainfall gauge |

7 |

|

Dik-dik are more difficult to detect because of wild dogs |

Detection distance is the same following wild dog recovery |

Detection distance |

Derived from distance sampling surveys (1999–2002; 2008–2013) |

Wild dog recovery status |

Telemetry and field observations of pack biomass and occupancy |

8 |

H2 - main |

Dik-dik suppress trees |

Trees will be more abundant in the absence of dik-dik than in the presence of dik-dik |

Net difference in density of trees in the 1.0–2.0 m height class (individuals∙100 m-2∙yr-1) |

Tree census in 2009 and 2012 |

Dik-dik access (MESO vs. TOTAL) |

Size-selective herbivore exclosure that either allows dik-dik, but not larger browsers, or excludes dik-dik and larger browsers |

9 |

H3 - main |

The effect of dik-dik on tree abundance is reduced in the presence of wild dogs |

The net difference in density of trees between exclosures and controls is greater pre-wild dog recovery than post-wild dog recovery |

Net difference in density of trees in the 1.0–2.0 m height class (individuals∙100 m-2∙yr-1) |

Tree census in 2009–2012, and in 1999–-2002. |

Ungulate access (OPEN vs. TOTAL) |

Exclosures that allow all (OPEN) or no (TOTAL) ungulates |

10 |

H3 - alternatives |

Browsers other than dik-dik suppress trees |

The density of browsers other than dik-dik is the same or greater following wild dog recovery |

Biomass density of browser pre and post-wild dog recovery |

Distance sampling surveys (1999–2002; 2008–2013) |

Wild dog recovery status |

Telemetry and field observations of pack biomass and occupancy |

NA |

|

Rainfall limits tree abundance |

Rainfall increased following wild dog recovery |

Monthly rainfall |

Rainfall gauge |

Wild dog recovery status |

Telemetry and field observations of pack biomass and occupancy |

11 |

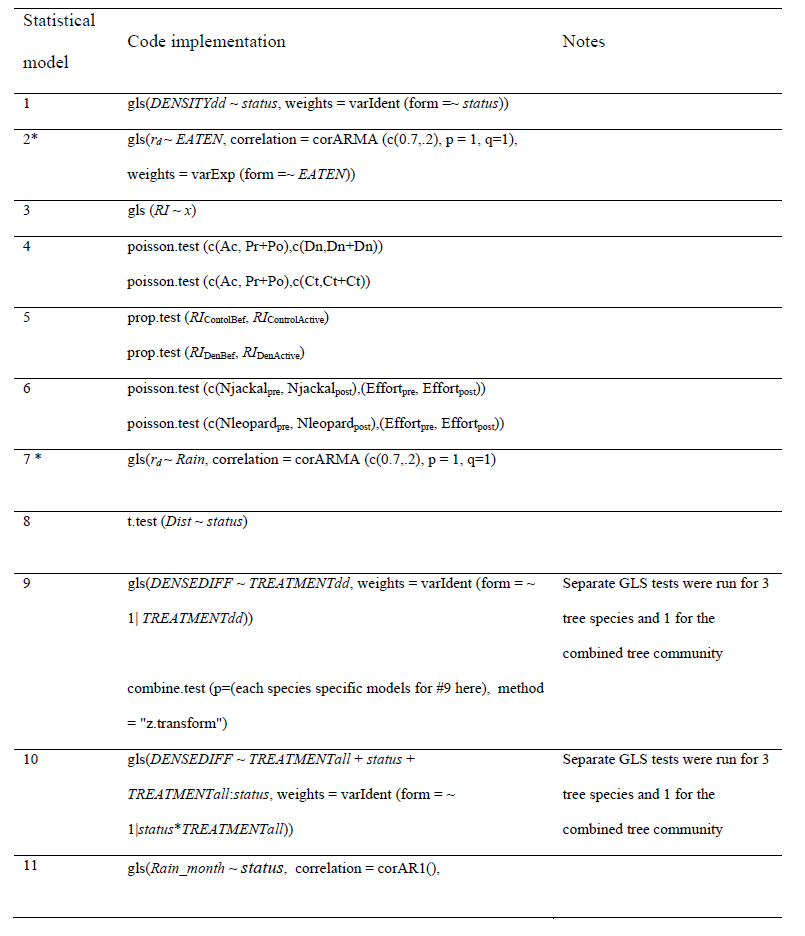

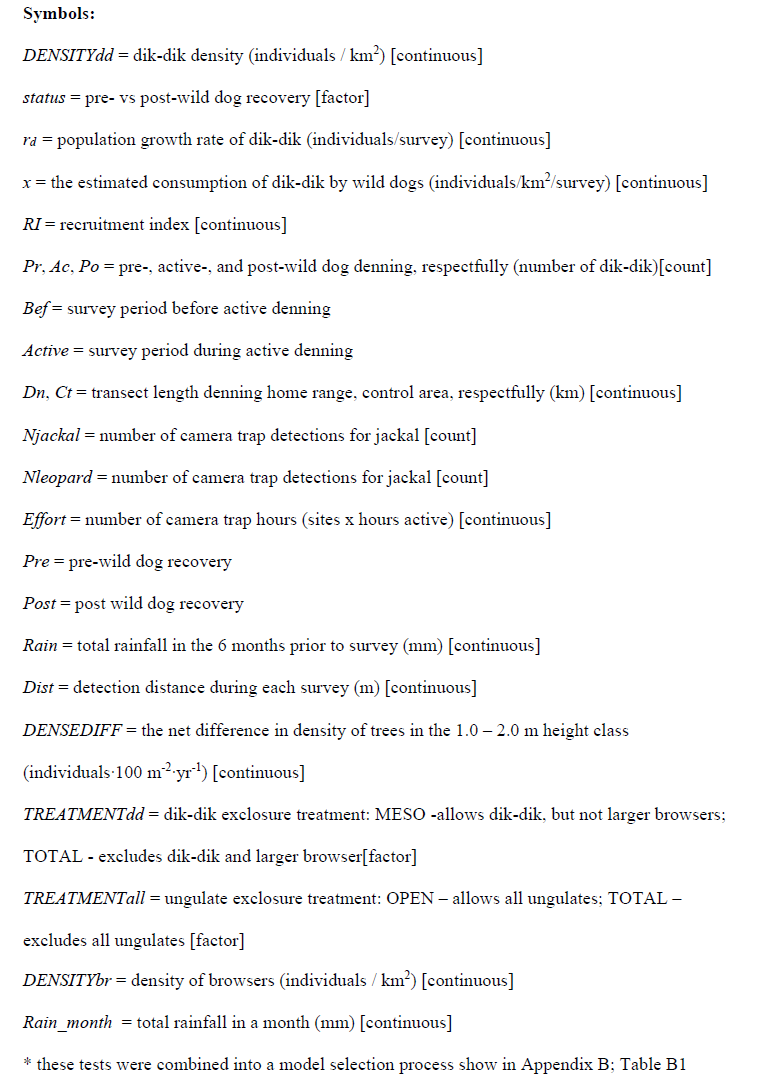

* See Table A2

Table A2. Structure of statistical models.

Literature cited