Appendix B. Morphometric character description and images and accompanying notes on their possible ecological relevance.

| No. |

Character |

Description |

Image |

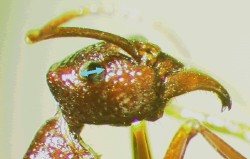

| 1 |

Distance

between eyes |

The

shortest distance from the inner edge of one eye to the inner edge of the

other eye. |

|

| 2 |

Length

of eye |

The

longest antero-posterior axis of the eye. |

|

| 3 |

Length

of mid-femur |

Length

of the femur of the middle leg. |

|

| 4 |

Landmark

1 to landmark 2 |

The

distance between Landmark 1 and Landmark 2 of Crozier et

al. (1986). Landmark 1 is the suture intersection between the pronotum,

the upper mesonotum, and the central mesonotum. Landmark 2 is the propodeal

spiracle. |

|

| 5 |

Landmark

1 to landmark 5 |

The

distance between Landmark 1 and Landmark 5 of Crozier et

al. (1986). Landmark 1 is the suture intersection between the pronotum,

the upper mesonotum, and the central mesonotum. Landmark 5 is the suture

intersection between the propodeum, central mesonotum and lower mesonotum. |

|

| 6 |

Landmark

3 to landmark 4 |

The

distance between Landmark 3 and Landmark 4 of Crozier et

al. (1986). Landmark 3 is the suture intersection of the pronotum, the

central mesonotum, and the lower mesonotum. Landmark 4 is the lowermost

point of suture intersection between the lower mesonotum and the propodeum. |

|

| 7 |

Length

of petiole |

Longest

antero-posterior axis of petiole node. |

|

| 8 |

Length

of scape |

Length

of the antennal scape. |

|

| 9 |

Weber's

length |

Distance

from the anterodorsal margin of the pronotum to the posteroventral margin

of the propodeum (Brown 1953). |

|

A Note on the selection of morphometric

characters used in this study:

We accept that, while

there is a relationship between morphology and ecology, it is not necessarily

true that all characters will be equally involved in competitive interactions.

It also follows that overdispersion in a character may not be attributable solely

to interspecific competition. We find it difficult, however, to establish apriori,

firstly, the ecological significance of a character, and, secondly, its involvement

in competitive interactions. This is particularly true for species (or OTUs)

whose natural history is largely unknown. We have therefore, taken an agnostic

attitude as to the ecological significance of the characters, or combinations

thereof, and simply ask whether the character set, as a multidimensional whole,

exhibits overdispersion (relative to a null model) in our test assemblages.

While our agnosticism allows us to work with these relatively poorly known organisms,

it greatly complicates interpretation of the observed patterns of overdispersion

as being the result, principally or exclusively, of interspecific competition

over ecological and evolutionary time scales.

Despite our reservations, we have some confidence in the character set as a

reflector of the varying ecological strategies of the OTUs. In a Principal Components

Analysis of all the measured specimens, all the characters were positively correlated

with the first principal component, which itself comprised 90.86% of the total

variance (see Appendix C). This indicates to us

that the character set as a whole largely reflects variation in body size -

a trait widely recognised as ecologically significant. Additionally, we envisage

several characters (1, 2, and 8) playing a role in the foraging strategies of

the OTUs, while the length of the middle femur probably plays a role in foraging

range.

LITERATURE

CITED

Brown, W. L. Jr. 1953. Revisionary studies in the ant tribe Dacetini. American Midland Naturalist 50:1–137.

Crozier, R. H., P. Pamilo, R. W. Taylor, and Y. C. Crozier. 1986. Evolutionary patterns in some putative Australian species in the ant genus Rhytidoponera. Australian Journal of Zoology 34:535–560